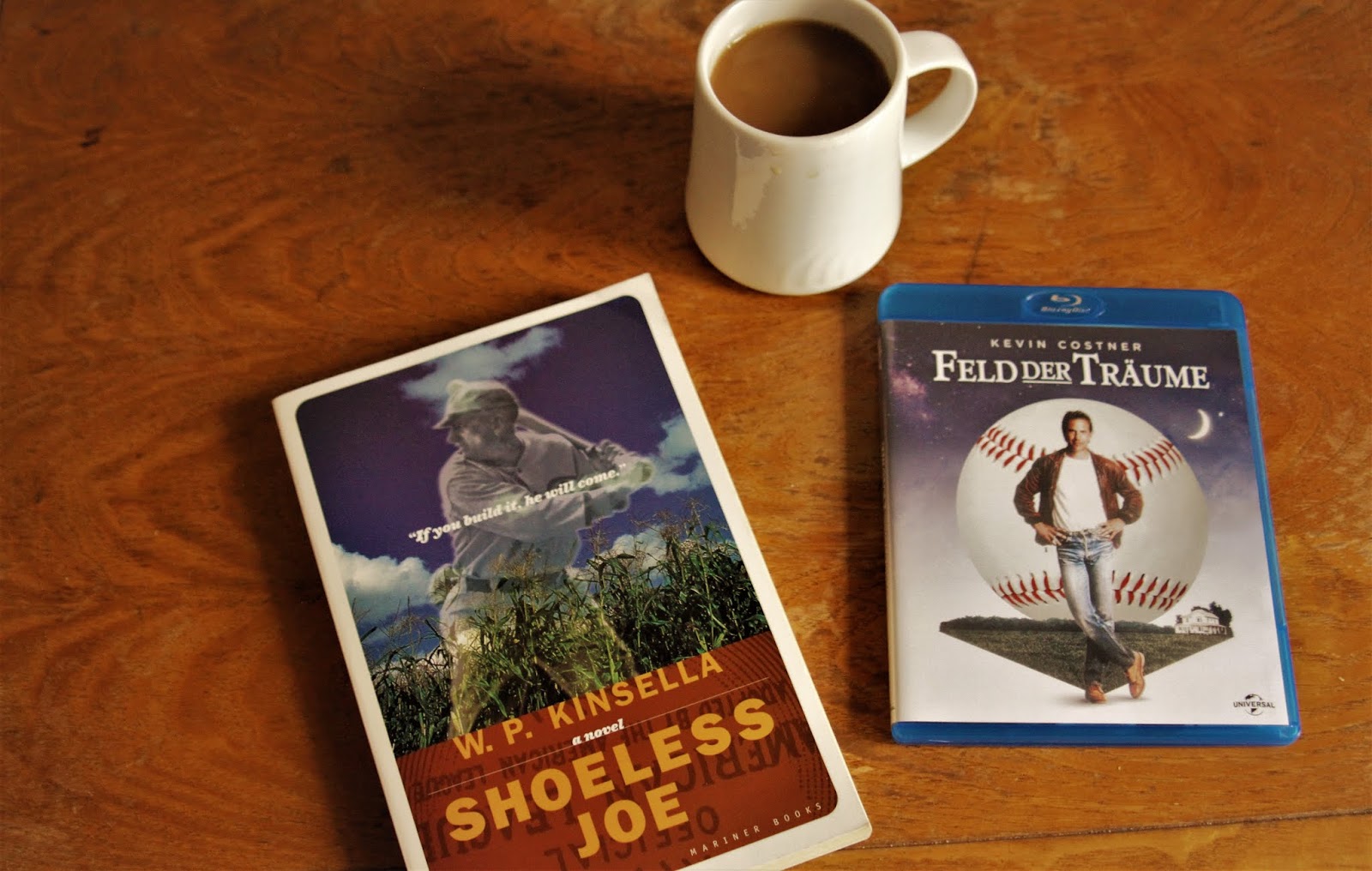

Deutsche Version des Interviews HIER / German translation of interview HERE

Back in the Nineties, I came across a comedy on German television starring Bill Pullman that was called U-BOOT ACADEMY – a film that seemed to be in the same vein as the POLICE ACADEMY movies, with lovably goofy characters and a delightfully silly kind of humor. Even though Michael Winslow had a small part in it, the film actually didn’t have anything to do with the ACADEMY series, as I later found out – its original title was GOING UNDER. Regardless of its connection or lack thereof to the ACADEMY movies, I loved the film – its visual gags, its crazy ideas, its Zucker-style absurdity. Pullman was in his wonderful early comedy mode, and the film (which I’ve always seen in its dubbed version, which adds quite a lot of puns) remains endlessly quotable.

Over the years, I’ve always kept an eye out for other films made by GOING UNDER’s director, Mark W. Travis. While Mark has worked extensively in television and theatre, GOING UNDER remains his only feature film. However, Mark went on to become a well-regarded teacher, doing acting and directing workshops all over the world, and releasing several books on directing, e.g. THE FILM DIRECTOR’S BAG OF TRICKS. You can find out more about him on his website.

After revisiting the film a few months ago and writing about it (here – a German-language review, though, like most entries in this blog), I decided to contact Mark and interview him about the film. I was surprised to hear that there was a lot of behind-the-scenes drama in post-production, and the finished film isn’t what Mark wanted at all …

Click here to read the interview.

|

| The German DVD cover of GOING UNDER: „Now they’re diving again!“ |

Christian Genzel: What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when you think of GOING UNDER?

Mark W. Travis: Oh, the first thing I think of is disaster.

Really?

Oh yeah. But that’s because there were a lot of political and creative disasters that happened during the movie. By political, I mean within the studio system. The movie you see is not the movie I made. The movie I made was much better.

The movie was doing fine, it became a political football at Warner Bros. Not that I had anything to do with it, but the powers that be, executive directors and other people at Warner Bros., were using it to their own personal purposes. And that was a very, very painful journey for me. This was all during post-production.

In fact, to tell you the truth, Christian – it’s very hard for me to watch the movie, because I know what it was. So it’s hard for me to see scenes that go „oh, yeah …“, but the way we had that scene, that moment or those characters was so different than the way it is now – so that’s painful, too.

Was the movie longer in your version?

No, not longer, just different.

So the studio re-edited the movie?

What happened was: when Warner Bros. became interested in the movie, at first they were interested in what’s called a „negative pickup“. A negative pickup means they would guarantee us they would buy the movie and distribute it for a certain amount of money – after we make it. Let’s say they say $5 million or something like that, which means with that negative pickup, you can go to the bank and borrow $5 million – just like that, easy. That’s the way it started. Then Warner Bros. got more and more excited about the movie and decided they didn’t want a negative pickup, they wanted to produce it themselves. And then the budget tripled immediately – because as soon as Warner Bros. is producing something, everybody’s price goes up.

.jpg) |

| Robert Vaughn as weapons manufacturer Mr. Wedgewood. |

What was the budget on the picture?

It started out at around $3 million and ended up at around $10 million.

Wow.

And it was the same movie! The movie didn’t change at all. So we had $10 million, which means we had more money, but there were more people involved on the payroll than we really needed, and things were more expensive. But that was okay.

Then the two writers wanted to be producers on it, so Warner Bros. said, „okay, you can be producers“ – and these were two writers who had never produced anything. They didn’t really know what it meant to be a producer. And then Warner Bros. placed another producer on the project who was one of their people. What I didn’t know was that this was a producer who had been working for Warner Bros. for a long time, but at this point he was on his way out. They were thinking of getting rid of him. So they gave him one last project to see if he could prove himself as a producer. I didn’t know that, I just knew we had a producer. He was being tested with this project.

Then, when it came into post-production, there were huge disagreements between me and pretty much all the producers on how the film should be cut together. So I never really got to finish my cut, because then the producers stepped in, and the producers started making deals with the studio without telling me. They said, „Oh, don’t worry about it, we’ll re-cut it“. And the film was doing well, it was doing very well on previews and everything. But then Warner Bros. somehow got it into their head that this was a movie for children – which it’s not, it’s a movie for adults. It’s all adult humor, it’s not children’s humor at all. And they decided it should be for children. So the first preview we did that was run by Warner Bros. was all children in the audience. The film wasn’t finished, but it was finished enough to preview it.

I remember walking into the theatre, seeing all these children and going „My god, this is insane!“ They mostly were teenagers and younger. And they didn’t get it, they didn’t understand the movie at all. The parents that were with them understood it, but the children didn’t. I remember one horrible moment when I was talking to one of the executives from Warner Bros. He told me, „Mark, it’s a disaster. This preview is a disaster“. I said, „Of course it’s a disaster. This is the wrong audience“. And we had another preview coming up three or four days later for a different audience. I said, „Wait until you see it in front of the right audience“. He said, „No, this is the right audience. We will make it work for them“. That was the beginning of the end. From that point on, the studio and some of the producers that were on the film were working together behind my back to try to make it work for children, while I was trying to make it work the way it was written. It ended up somewhere halfway in between.

You can sense that in the finished film – there are still traces of political satire, almost STRANGELOVE-like elements, as with the Secretary of Defense, Mr. Neighbor, this Mr. Rogers-kind of guy who doesn’t have a clue about what’s going on, and Admiral Malice just pocketing all this money into his private bank account …

Yeah. Christian, even if you look at the names of some of the characters – Admiral Malice, General Confusion … children don’t understand that humor. They just go, „huhhh?“ (laughs) But the adults would get it. You’re right, it’s very subtle humor – it’s more along the lines of AIRPLANE! or BRAZIL or something like that. It’s very political – it was even more political than it is now. And yeah, DR. STRANGELOVE is a great example. One of my favorite films – because the humor in there, that’s also very cutting humor and also very political.

|

| Ned Beatty as Admiral Malice. |

There’s one scene where he’s with the psychiatrist, and there’s a flashback in that scene about the Bongo, the submarine. That whole flashback was a huge scene that we shot – the beaching of the submarine. It was a great scene. That was supposed to open the entire movie! The whole idea was to open the movie just like a James Bond movie, where you see your hero on his last mission. But our hero is claustrophobic and afraid of water, and it’s a disaster. And that was the way to introduce Biff Banner. We had it all cut together, and it worked great. I even put in „Thus Spake Zarathustra“ in the beginning, which was a nod towards 2001. They came and said, „You’re using music that was used in another film!“ I said, „Yes, there’s a point to that!“ I kept using music from other films just to make a reference to other films, and they said, „Why would you do that?“ A lot of people didn’t understand my sense of humor. But that opening sequence was fantastic, and it ends up with Biff Banner being hauled out of the submarine by a crane because he won’t let go of the periscope. It’s just silly, it’s stupid. But then they decided to make that a flashback by a third of the way through the movie, and I look at it and go (sigh). It pains me because I knew what we had.

I can understand that. Even though – I didn’t know that it was supposed to be at the beginning of the movie – I always thought it was a nice joke when he tells the psychiatrist, „It was my first command and everything went great!“, and then you cut to the chaos on the bridge, somebody yells „We’re about to crash!“, and he continues in the voice-over, „Well, not that great“. I never thought about the fact whether it was intended to be like that or not.

No, that was not the intention. Again, these two writer-producers really didn’t know … I mean, they never made a film before. So they didn’t know much about producing or editing, the whole editing process. And ironically – this is the political part, which I found out after the film was over – these producers were making deals with the studio to get another project going. And part of the deal was that they would take over this project. So it was all self-serving. And there was another producer who we learned later actually stole about fifty, sixty, seventy-thousand dollars out of the budget so he could buy a ranch. So there was a lot of messy stuff going on.

Both of the writers, I think, never made another movie. I think Randolph Davis has a credit on the seventh POLICE ACADEMY movie, but the other one – at least from what I see on IMDB … I tried to google him and I have no idea where he ended up.

I don’t know. Neither of them have made a movie since. The sad thing is they were in a good position to set themselves up to make the movie. And people in the studio are not stupid. They start making these deals with young producers like that – they know what the producers are doing, the producers are trying to leverage one film against the other, and studios don’t really like that. So there’ll be a lot of talk and then nothing happens. And the one producer that was on it that was from Warner Bros., when the film was over, he was fired. The end was sort of a disaster. Not a happy experience at all.

That kind of takes care of the question whether it was fun to shoot the movie …

No, it was! We had a great time shooting. While we were shooting, the studio pretty much left us alone, except for some inside stuff that the producers were doing. I could do whatever I wanted to do, which was nice. We had a great time shooting the film. I kept hearing from producers from other films that were done at Warner Bros., and some of them would go in and watch the dailies from my film. They said, „We love it! We’re gonna watch the dailies all the time because it’s such goofy, silly stuff you’re doing!“ So while we were shooting, everything was great. There were no problems. Everything looked great, everybody was happy. It was once we hit post-production that things were going badly.

That really must have hurt.

Yeah, it did.

.jpg) |

| Biff Banner (Bill Pullman) being hauled out of the sub by a crane. |

So how did you get involved with the project in the first place?

A good friend of mine, who’s actually in the film – Dennis Redfield, who plays Turbo – he knew these two writers, somehow he’d become connected with them. He knew about the project, and he recommended me to them. Dennis and I have worked on several projects together over many years. So that’s how I met them. Also, at the same time, I had a play that was running that I had developed and directed – a one-man show called A BRONX TALE, which eventually became the movie A BRONX TALE. This play was really, really popular. It was sold out for months and months. And the studios were all scrambling to try to buy the rights to the play to make the movie. Chazz Palminteri and myself – Chazz was the actor and writer in the play, I was the developer and director, and it was his story – so he and I decided to see how long we can hold out without selling it to the studios to see if we can get the price up. We brought in another producer who helped us finance the play, and we took it to New York, all that kind of stuff.

Point is, during that period of time, if you were attached to a piece of property that the studios wanted, you could pick up the phone and probably get any studio you wanted, immediately. So I used that, and I would pick up the phone and say, „My name is Mark Travis, I’m with A BRONX TALE …“ – „Oh yeah, Mark, how are you?“ You know. „Can I have a meeting with so-and-so? It’s not about A BRONX TALE, it’s about another project.“ – „Of course you can!“

Then half of the conversation would be about A BRONX TALE – „How is it going? What are you going to do?“ But that was just an easy entry. So that’s how we got into Warner’s and a lot of other studios. And Warners seemed the most enthusiastic about GOING UNDER, which was called DIVE! at that point … which is a better title. But the reason they had to change the title was that Steven Spielberg was going to open a restaurant called „Dive“. They didn’t want to make a movie that would support his restaurant … Eventually, A BRONX TALE was sold to Universal and Tribeca. So that’s how it got set up – rather easily. It was because of other issues.

Did you do a lot of work on the screenplay with the two writers, or was the script more or less finished when you got it?

The screenplay was more or less finished. We did a lot of work – and to tell you the truth, Christian, I know now we should have done a lot more. It’s hard to tell from just looking at the film. My whole focus is on story, characters and character relationships, and the writers‘ focus was more on jokes. They loved to write jokes, and I would say, „That’s a great joke, but if it’s not connected with the story or isn’t moving the story forward, it’s just a joke.“ So that were some of the problems we had, but while it was in development at Warner Bros., we did maybe three or four rewrites, I think. And knowing what I know now, many years later, because I know a lot more about screenwriting and storytelling and all that, I look at it and think we could have done so much better if we had spent more time on the script. It could have been better, it could have been funnier. It could have been more political and more cutting.

|

| Dennis Redfield as Turbo, the submarine’s engineer. |

What about the visual gags and the production design gags? Were those in the script or were they developed on set?

You’d have to tell me which ones.

A lot of stuff, like the „seal of approval“ which is behind Secretary Neighbor’s desk, or the logo of Wedgewood Industries, „National Defense at Your Expense“, or when they jump over the iceberg and they’re suddenly doing a sleigh ride, wearing wool hats and there’s snow on the bridge …

Yeah, a lot of that was in the script. That was the whole general idea of the whole movie – wacky, really, really wacky humor. And during the rewrites a lot of these things got developed more. If you look at Wedgewood’s, the name of the company was WRT. That’s TRW backwards – and TRW at that time was a massive technology industry. There are a lot of things in there that you may not get – they’re very subtle things. But a lot of that humor was definitely in the script.

What about the casting process? How did all the actors come on board, how did Bill Pullman get involved?

Bill Pullman is an actor that I knew – I didn’t know him well, I do now, he’s a good friend now. I’ve seen a lot of his work both on stage and in film, so we went after him and got him. We had trouble casting the female lead because a lot of leading actresses didn’t want to do it – I think they felt afraid of it because of the humor. Ned Beatty was someone that I also knew about but didn’t really know that well, and I knew he would be perfect for what I wanted. Roddy McDowall – when we came up with the idea of Secretary Neighbor and who could play him, immediately I thought of Roddy McDowall, and I had no connection with him whatsoever. But we went after him and he just loved the crazy idea and the politics of that. And they were all fantastic to work with.

A lot of the other characters on a lower level were my friends. People I’ve known because I’ve worked so long in film, television, and mostly in theatre. So I brought in a lot of my friends – so I would have friends on the set, I like that.

|

| Bill Pullman and Wendy Schaal. |

What about Michael Winslow? Was he the studio’s idea?

He may have been … or one of the producers‘. I liked it because of his verbal ability. Any time I can get someone wacky in there … I think it was a studio idea.

One day I got a call from the studio, it was one of the executives, and the call literally went like this: „Don Rickles.“ – „Yeah, what about him?“ – „He’s in your movie.“ I go, „What?“ – „Don Rickles is in your movie.“ Now, the only part he probably could have done was Ned Beatty’s part, Admiral Malice, and that was already cast. I say: „What part?“ – „I don’t know! He’s in your movie.“ It took me about a week to get him out of the movie! There was no place for him. But the studio would do this many times. They would just throw some comic or comedian at me and say, „Put him in the movie“. They didn’t have an idea about what part or anything, they just wanted these names in the movie.

You’re probably aware that in Germany, the movie is marketed as a sort-of POLICE ACADEMY follow-up. It’s called U-BOOT ACADEMY. That’s why I asked about Michael Winslow, he’s sort of the tie-in to the POLICE ACADEMY movies.

Exactly.

What about the process of actually shooting the film? Did you rehearse a lot?

Yeah. Because my whole background is theater, I do rehearse a lot. We only had about a week of rehearsal before we started shooting, which is not a lot for me. I’d rather have two or three weeks. But I rehearsed a lot on the set, too. I can rehearse very fast. But it needed that rehearsal because of the rhythms and the humor and just the general attitude. And most of the cast comes out of theater – Bill Pullman’s out of the theater, Wendy Schaal’s out of the theater, all of them work in theater, which means they know how to rehearse and they can hold on to an idea for a long time, they can retain a rhythm or a tone even for a whole movie.

|

| Michael Winslow as a reporter. |

Did you allow the actors to improvise?

Yeah. It depends on the scene – sometimes I would, some of the scenes are improvised.

For example?

There’s a whole sequence – I can’t remember what’s left of it. There was one time where we were sitting on the set, shooting something, and I came up with an idea. It was with Ned Beatty and Roddy McDowall. And Roddy McDowall being British, obviously, didn’t understand football (laughs). There’s a whole sequence where they’re watching the football thing on the screen, and there’s the whole sequence where Joe Namath says „punt“ – and Roddy actually said to me, „What’s a punt? What is it?“ And Ned Beatty was explaining it, and I said: „Stop! Stop! Get the cameras here quickly!“ And we filmed the whole conversation between the two of them, which was totally improvised – „What’s a punt? Why do they do that, it doesn’t make sense?“, and Ned Beatty tries to explain it. To me, those are the kind of things I would have loved to do more of, to find those moments of humor between the actors where they could improvise. We did it as much as I could without going over budget or getting way off script, but I wish we had done more.

I noticed in a lot of scenes, you often have several actors in one frame so you can get a feel of their interaction. And some of the interactions feel like they were made up on the spot, like when Bill Pullman and Wendy Schaal wear these ridiculous hats with the long visors, and they both try to put theirs on top – and Wendy’s gets stuck and she gets angry and takes it off.

That was actually rehearsed! Just to work out the logistics of it. But then it’s rehearsed enough that we can let it go loose and let them improvise within the rehearsal, so it looks totally improvised. That’s what I want, I don’t want it to look rehearsed at all.

The other thing you said about the framing – if you have several people in the frame, there are two things that happen: one is, the audience is immediately aware, as long as you’re not doing a lot of cutting, that this thing is playing in real time and you’re really watching them more like a play, you’re watching them play with each other. And also, you can allow them to overlap, which I like. Almost everything I do, there’s overlapping dialogue. I like the dialogue to get messy. Just like you and I, even in this conversation, we interrupt each other and overlap each other – that’s the way people talk.

There are a number of nice long shots in there which don’t really draw attention to themselves, like when Biff Banner enters the U-boat and meets the crew – a lot of this is just one long shot. I like those scenes where you feel that events unfurl in real time and you see real interaction.

|

| Ned Beatty (left) and Roddy McDowall as Admiral Malice and Secretary Neighbor. |

Do you have a DVD of this movie or a videotape?

I have a VHS tape. It did come out on DVD in Germany, with only the German audio track on it, but I think it’s out of print now.

Probably.

And I’m not aware of any other international release of the movie.

It will always remain an obscure movie.

It’s very sad, actually.

I know (laughs).

Even when you tell me it could have been much better, I still think it’s a movie with a lot of good stuff in it. It’s still very funny, and it’s just my kind of humor, I guess – I like this absurd kind of humor which is very creatively done. Was there anything you wanted to do but couldn’t because of budget or time?

Ahh … I was going to say „no“, but that’s not true. Yeah, there were a lot of things I couldn’t do because of budget. I would come up with these visual jokes – there was one scene, I forget which scene it was, it takes place on the Sub Standard. It was a meeting. I remember reading the scene, I said, „Oh, I want to stage this like the Last Supper“. I had this whole plan so I would have everybody behind the table, with Biff Banner right where Christ is, and I was even going to have moments of a freeze-frame that would actually replicate the Last Supper – which was a great idea, but the cost of building that set for just that scene somehow became prohibitive, so I couldn’t do it. So there were things like that – a lot of times I would come up with visual ideas that were just too expensive, way too expensive. The budget wasn’t that big, it was a small, tiny budget.

I wanted much better miniature work than we got – I was never happy with the miniature work, the Sub Standard and all that. But this is what frustrated me – when I kept getting told, „We don’t have the money, we don’t have the money“, and then I find out one producer was stealing money from the budget. And he was the one who was telling me we have to cut sets, we have to get rid of a couple of sets! He got rid of some of the money anyway. But basically, it’s a performance piece, so even though there are a lot of visual jokes in it, it’s performance – and performances are not expensive. As I said before, I wish we had spent more time on the script, because I think we could have done a lot better.

|

| Bill Pullman, Wendy Schaal and Lou Richards (from left to right). |

But the biggest frustration was not being allowed to finish it – at one point, deep into post-production, I’m looking at the film and I’m going, „There are too many things that are not making sense in the beginning“. And the audience is scrambling for what’s really going on here. I know enough about filmmaking to know that one solution to that problem in any film is narration. It’s done all the time. AMERICAN BEAUTY did it, and that won an Academy Award. I came up with this great idea, and I wrote it, too: the film is narrated by Roddy McDowall’s character, and he’s telling the story of Biff Banner and the Sub Standard very much like Mr. Neighbor would tell it to children. You know, „Once upon a time, there was this woooonderful captain, but he had a problem …“ (laughs)

And I wrote this whole narration that I wanted to use very sparingly at the beginning and the end of the film. I thought this was great, and it showed it to the editors, and everybody got excited about it. The studio went, „No, no. That’s it. We’re going to finish the picture the way we want it, we’re not doing any more.“ They didn’t even want to pay Roddy McDowall for a day to come in and record the narration. That was frustrating, because that was a moment where suddenly I thought, now I can bring it to another level. And I thought the studio would be happy, because his tone and voice would appeal to children! Or the child within all of us. It would give the whole thing a special tone, and his character was perfect for this – because he was really an observer to the chaos, and a naïve observer. I fought and fought and fought for it, and they went, „No, no, no, no, no. We’re finishing it.“

The sad thing – now, this was much later, months after it was done – when I was talking to a lot of my other friends about it because they were all concerned about what’s going on. They knew what was going on while I was making it. And one of them said to me: „You know the biggest problem, Mark?“ I go, „No?“ – „You were at the wrong studio. If you’d been at Disney – Disney is known for hanging in with the film until they can make it the best it can possibly be. Warner Bros. is known for finishing it up quickly to try to save money and just put it out there and move on.“ They said, „If you’d been at Disney, you would have gotten the film you wanted.“ But that’s hindsight – „that’s great, that doesn’t help me!“ (laughs) But it’s an education.

So if you had the chance, would you like to revisit the film and cut it together the way you wanted to do it? Release a director’s cut?

Oh, I would love to do that. I’d have to get back into all that footage again … yeah, that would be great. Truth is, if someone let me do that, I would bring in someone who could do Roddy McDowall’s voice and I would do the narration. All I need is the voice, someone that sounds like him. Then I can make it the way I wanted it.

Any chance of that happening?

No. I’d have to go to Warner Bros. and say „I want all the footage“. That was all shot on film – who knows where all that footage is now. Then I’d have to pay an editorial team to reassemble it. I mean, Warners isn’t going to do it. So there’s no chance of that. The only chance would be if I had all the material – truth is, I do have all the material … on VHS, with timecode on it. That’s the dailies with running timecode. But I’m not going to take it and do it with that, that would just be messy. Unless you want to finance that, Christian …

If I had the money, I actually would do it!

All the footage is there. You wouldn’t have to shoot anything else.

|

| Bill Pullman and Ned Beatty. |

Did you see the film DOWN PERISCOPE with Kelsey Grammer?

No, I didn’t.

It came out a couple of years after GOING UNDER, and I always felt that they must have watched GOING UNDER. There’s a lot of stuff in there which is similar to your movie.

Oh, really?

Yeah, there’s the whole set-up with an incompetent captain on some sort of wacky mission, and there’s a woman on the U-boat who’s from some sort of academy, she’s in a supervising position. All these sorts of things. It’s a funny movie, Kelsey Grammer is very funny, but I think they took some inspiration from you.

That’s nice. I think when it came out, I thought „I don’t want to see it“ (laughs).

You’d had enough of submarines.

Yeah, I’d had enough.

Were those problems the reason there was never a second theatrical feature film for you?

Yeah, that put an end to my filmmaking career for a long time. That’s the Hollywood system. You make a film, and then people say, „Okay, you made a film, how did it do? How much money did it make on the first weekend?“ They didn’t even care about seeing the film. „Well, it didn’t make a lot.“ – „Well, okay, then we’re not interested in you.“ Or they hear that it was a film that basically Warner Bros. put on a shelf – I mean, they released it, but that’s it. It was mostly released on VHS. You hear that and it’s a major studio, so they go, „Okay, must’ve been a disaster, we’re not going to hire him“, and they move on.

For a period of time, when I was making the film, when all the reactions to all the footage were so positive, other scripts were being sent to me. I thought, „That’s great, but I don’t have time to read them, I’ll read them later“. After the film was over, suddenly it went quiet. So it’s true: it’s all based on what your last film is.

Would you be interested in doing another comedy?

Oh, sure! And I’ve done a lot of television since then. I just did another film a few months ago, a short film which is a pilot – we’ll see what happens with that. I have a couple of other films I’m looking at doing – hopefully, one of them this year. Now it’s a matter of raising money.

Sounds good! It’s something to look forward to.

Absolutely!

.jpg) |

| Bill Pullman as football-captain-turned-submarine-captain Biff Banner. |

Did you learn a lot from GOING UNDER which you can now use when you teach film or consult filmmakers?

Oh yeah. I made a lot of mistakes because it was my first feature film. Almost immediately, because I couldn’t get another film going, I started teaching – and the teaching just took off. It’s become my main career for many years. Lots of times I go, „What am I doing, what happened to filmmaking?“ And then I realized what I was doing unconsciously: I was teaching myself how to make a better film. So I’ve learned a lot from GOING UNDER, and from other films I’ve worked on, where I wasn’t the director, where I was a consultant or an acting coach – I learned a lot from those, too. It’s affected my teaching a lot and it’s affected my directing a lot.

In a way, I created the best film school – at least the best film school for me, which is to go out and try to teach everything, even teaching things I don’t know, things I don’t understand. The challenge with film directing is there’s so much you really need to know, and it’s impossible to know all of it. There’s just no way. It’s such a huge, complex and actually dangerous job – dangerous because it’s very easy to make a mistake (laughs) and then find out in post-production, „Oh god, I made a mistake!“ It’s so easy to mess it up.

And there’s a lot of money on the line, too.

Yeah, a lot of money on the line, and it’s a wonder that any film comes out good. It’s easy to make a bad film.

Mark, thanks a lot for taking the time to talk about the movie, even if you say it’s a painful experience or a painful memory …

It’s a painful memory, it’s not a painful experience to talk about it. I like talking about it because there a lot of fond memories – we had a great time shooting the film, and a lot of post-production was fun. Then it got messy. But it was a good experience, I’m glad I had it.

I suppose that happens on a lot of films and you just don’t know about it – there are a lot of films which remain obscure, where you don’t read a lot about them, and if you talk to the filmmakers they would probably tell you that something went wrong with the studio or in post-production …

Yeah, I’m not the only one. I talk to so many directors who go, „Oh yeah, I got a story like that“. And some of them are worse. Being fired off the movie halfway through and things like that. It shouldn’t happen to anybody, but it happens a lot.

And I’d like to say, Christian, I really appreciate you and your enthusiasm for the film. I rarely hear about the film, and rarely anybody talks to me about it. So it’s a pleasure and a delight to talk to someone who goes, „Oh, I like this film!“ Thank you! Even though it’s not the way I wanted it to be, the fact that it still comes through is nice. That’s very gratifying, so I thank you.

Photo of Mark W. Travis (C) Mark W. Travis